George Hay (Virginia judge)

George Hay | |

|---|---|

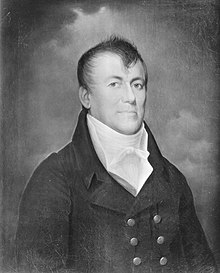

portrait by Cephas Thompson | |

| Judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia | |

| In office July 5, 1825 – September 21, 1830 | |

| Appointed by | John Quincy Adams |

| Preceded by | St. George Tucker |

| Succeeded by | Philip P. Barbour |

| Personal details | |

| Born | George Hay December 17, 1765 Williamsburg, Colony of Virginia, British America |

| Died | September 21, 1830 (aged 64) Richmond, Virginia |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Relatives | James Monroe (father-in-law) |

| Occupation | Judge |

George Hay (December 17, 1765 – September 21, 1830) was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.

Education and career

[edit]Born December 17, 1765, in Williamsburg, Colony of Virginia, British America,[1] Hay read law.[1] He entered private practice in Petersburg, Virginia, from 1787 to 1801.[1] He continued private practice in Richmond from 1801 to 1803.[1] He was the United States Attorney for the District of Virginia from 1803 to 1816.[1] He was a member of the Virginia House of Delegates from 1816 to 1822.[1] He resumed private practice in Washington, D.C. from 1822 to 1825.[2][1] Hay was a close confidant to his father-in-law, James Monroe, especially during the Missouri Crisis. During the Crisis, he anonymously penned a series of pro-slavery essays for publication in the South's leading newspaper, under the title, "For the Enquirer. Missouri Question."[3]

Notable case

[edit]During his service as United States Attorney, Hay served as prosecutor during the trial of Aaron Burr.[4]

Advocacy

[edit]Hay was an advocate for freedom of the press, and became known for his defense of James T. Callender at Callender's Sedition trial.[5]

Hay became a strong advocate of slavery and authored a series of heavily proslavery pieces during the Missouri Crisis under the penname of "An American."

Federal judicial service

[edit]Hay received a recess appointment from President John Quincy Adams on July 5, 1825, to a seat on the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia vacated by Judge St. George Tucker.[1] He was nominated to the same position President Adams on December 13, 1825.[1] He was confirmed by the United States Senate on March 31, 1826, and received his commission the same day.[1] His service terminated on September 21, 1830, due to his death in Richmond.[1]

Family

[edit]In 1808, Hay married Eliza Kortright Monroe, daughter of President James Monroe. They had one child whom reached adulthood, Hortensia. [6]

Quotes

[edit]- It is obvious in itself and it is admitted by all men, that freedom of speech means the power uncontrouled by law, of speaking either truth or falsehood at the discretion of each individual, provided no other individual be injured. This power is, as yet, in its full extent in the United States. A man may say every thing which his passion can suggest; he may employ all his time, and all his talents, if be is wicked enough to do so, in speaking against the government matters that are false, scandalous, and malicious; but he is admitted by the majority of Congress to be sheltered by the article in question, which forbids a law abridging the freedom of speech. If then freedom of speech means, in the construction of the Constitution, the privilege of speaking any thing without controul, the words freedom of the press, which form a part of the same sentence mean the privilege of printing any thing without controul.[7]

- A citizen stands safe within the sanctuary of the press, if he should endeavour to prove that there is no God, or affirm, that there are twenty Gods: If he condemns the principle of republican institutions, and contends, that liberty and property can never be secure, but under the protection of aristocracy or monarchy: If he censures the measures of our government, and of every department and officer there-of, and ascribes the measures of the former, however salutary, and the conduct of the Matter, however upright, to the basest motives; even if he ascribes to them measures and acts which never had existence; thus violating at once, every principle of decency and truth.[8]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k George Hay at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- ^ "O Say Can You See: Early Washington, D.C., Law & Family". earlywashingtondc.org. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- ^ “President, Planter, Politician: James Monroe, the Missouri Crisis, and the Politics of Slavery,” Journal of American History, 105 (March 2019), 843 – 867

- ^ Adams, Henry. History of the United States of America during the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson. The Library of America Edition. p. 909.

- ^ Slack, Charles (3 March 2015). Liberty's First Crisis: Adams, Jefferson, and the Misfits Who Saved Free Speech. Open Road + Grove/Atlantic. ISBN 9780802191687 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Eliza Monroe Hay". Academics | Papers of James Monroe. University of Mary Washington. Retrieved February 10, 2024.

- ^ An essay on the liberty of the press, p. 32

- ^ An essay on the liberty of the press, p. 66

Sources

[edit]- George Hay at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- An essay on the liberty of the press: respectfully inscribed to the republican printers throughout the United States, 1799.

- "O Say Can You See: Early Washington, DC Law & Family Project". Center for Digital Research in the Humanities.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- 1765 births

- 1830 deaths

- Members of the Virginia House of Delegates

- Judges of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia

- United States Attorneys for the District of Virginia

- United States federal judges appointed by John Quincy Adams

- 19th-century American judges

- Politicians from Williamsburg, Virginia

- Monroe family

- United States federal judges admitted to the practice of law by reading law